A 16-year-old boy presented with IBS-like symptoms of chronic abdominal pain and diarrhoea. A clinical diagnosis of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) was made.

Hydrogen Breath Test

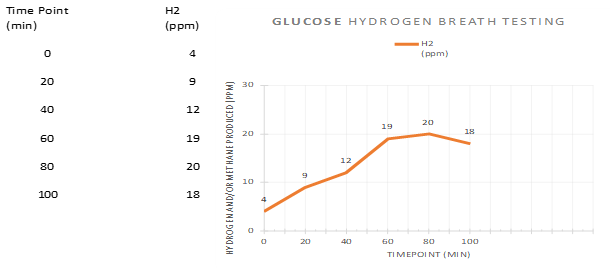

A hydrogen breath test was carried out using 75g of glucose, the patient had followed a restricted diet the previous day and fasted overnight. Methane levels in the breath were not analysed.

The results showed an increase in hydrogen to 20 ppm in 80 minutes.

Interpretation and Next Steps

Based on the results obtained, the clinician considered the rise in hydrogen to 20 ppm as ‘positive’ and prescribed a 10-day course of rifaximin as a treatment for SIBO, after which the symptoms subsided. A month later, the treatment was repeated.

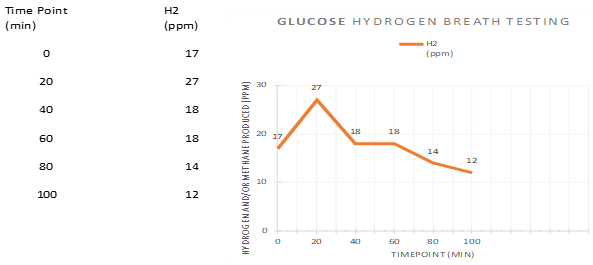

However, a week after the second course of rifaximin was completed, the symptoms returned. A second hydrogen breath test was carried out one month after the end of the second rifaximin course.

Case Analysis

- Age

The patient was 16-years of age and therefore on the border between childhood and adulthood. If his physical measurements i.e., height and weight are considered close to that of an adult, he may be assessed as an adult in terms of testing and interpretation protocols. If the patient is to be considered a child, performing and interpreting breath tests would be difficult as there are no consensus guidelines for paediatric cases - Alternative Clinical Diagnosis

Based on the patient’s history of IBS-symptoms, such as chronic abdominal pain and diarrhoea, it would make sense to test for carbohydrate malabsorption e.g., lactose or fructose – if SIBO were ruled out as a cause of the symptoms. - Inappropriate/Incomplete Test

According to the North American Consensus 2017(1) for breath testing guidelines for adults (Fig 3), lactulose is a non-digestible disaccharide that reaches the large bowel. The sugar is therefore able to travel and scan the entire length of the intestines is subject to fermentation by bacteria it comes into contact with. Therefore, lactulose is able to detect both proximal and distal SIBO. In contrast, glucose is a monosaccharide that is absorbed in the proximal small intestines and therefore cannot detect distal SIBO. Overall, although not specifically advised by the North American Consensus, using lactulose is favoured over glucose in the investigation of SIBO.- Lactulose is more specific but less sensitive than glucose in detecting SIBO i.e., the diagnosis made is more accurate.

- Quantity of sugar to be ingested for lactulose test is 10g (as opposed to 75g for glucose), making it more practical and manageable for patients to consume.

The degree and quality of evidence is higher for the use of lactulose (rather than glucose) to test for SIBO (Fig 3).

4. Missing Information

Methane levels in the breath were not measured. The test would have been more complete had the clinician also measured methane levels. Such a test would have indicated whether or not the patient was methanogenic, which might have contributed to his symptoms.

5. Incorrect Diagnosis

The result of the first breath test was incorrectly diagnosed as SIBO by the clinician, as they considered a rise of hydrogen to 20 ppm within 90 minutes as being positive without considering the rise from the baseline hydrogen level of 4 ppm.

6. Transient Response

The transient response to rifaximin could possibly be due to treating:

- Discomfort caused by excessive methane production, which wasn’t tested for.

- Distal SIBO

- Carbohydrate malabsorption

- The placebo effect

7. Retesting

A second course of antibiotics was administered a month after the first, without re-testing for SIBO following the first course. It was a good decision (if the test was initially positive) to repeat the breath test 4 weeks after cessation of antibiotics, as this leaves sufficient time for re-colonisation of bacteria and re-development of SIBO. However, the second breath test was also inconclusive i.e., it did not suggest SIBO.

6. What Further Measures Can Be Taken?

- Repeat the breath test using lactulose as a test substrate.

- If the test is positive, treat with antibiotics (use paediatric doses per kg of body weight for a child).

- If the test is negative, test for carbohydrate malabsorption (e.g., lactose or fructose).

- Consider the first-line antibiotic treatment for SIBO.

- Amoxicillin-Clavulanate (Augmentin)

- Rifaximin (Xifaxan): 550mg/TDS/2 weeks (efficient in 80%)

- In cases of recurrence, use of combination of 2 – 3 different low-dose, long-term antibiotics (e.g., rifaximin, doxycycline and ciprofloxacin) rotated every two weeks to avoid resistance. Repeat for up to three cycles.

- Also, consider small intestinal aspirate with antibiotic sensitivity

- Treat SIBO’s underlying causes if possible. Unfortunately, such causes are often ignored and the patient keeps returning with recurrences of SIBO. Some underlying causes to consider are:

- Medication that impairs bowel motility leading to stasis of intestinal contents promoting bacterial overgrowth.

- Long term PPI use which suppresses gastric acid secretion and eliminates the first line of antimicrobial defence.

- Anatomical changes following bowel surgery or other causes that cannot be eliminated. In these cases, the patient will have to be re-treated whenever they become symptomatic.